Written by Lauren Villa and Brittany Giles

Imagine for a moment that you are a single, 27-year-old woman with two young children, six months pregnant…and homeless. The father of your unborn child is violent and prone to abusive behavior. You are unemployed and have difficulty finding sustainable housing. You hear about a local shelter that has a vacancy for tonight – they have food and there are mats where you and your children can sleep on the floor. At 8:00 am the next morning, you are required to pick up your belongings, and head back out to the streets. You wait until 4:00 pm when the shelter opens again, only to hear that there are no vacancies tonight. The stress of being a single mother and homeless takes its toll on you, and you worry about the health of your unborn child. You are scared to seek out prenatal care because you don’t have health insurance and you are afraid of what providers will think of you. You are depressed and continue to use alcohol and drugs throughout your pregnancy.

Homeless Women and Children Have Increased Health Risk

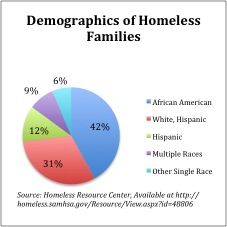

Homelessness has become part of the life experience for growing numbers of American mothers, children, and families. According to this annual report on homelessness in the U.S., on any given night in 2010, 407,966 individuals experienced homelessness in shelters, transitional housing programs, or on the streets.[i] Of homeless families in shelters, women comprise 77.9% of adults, with nearly 1.5 million children experiencing homelessness in any given year.[ii]

Moreover, research shows that homeless women are more likely to have:

- Acute and chronic medical problems,

- No regular source of care,

- Inadequate prenatal care,

- Higher rates of depression,

- Higher rates of childhood physical and sexual abuse,

- Experienced assault by intimate male partners, and

- High levels of stress. [iii], [iv], [v]

Given these risks, pregnancy is a time of particular vulnerability for the children of homeless mothers. Research has found that high levels of stress during pregnancy can result in a change in the normal development of the fetus, and persistent disparities in health outcomes among minority women are associated with stress.[vi] This is a burgeoning national problem, especially when we consider the life course of pregnant homeless women, many of whom are minorities and/or substance abusers.

What is the Life Course model and what does it mean for homeless pregnancy mothers?

For those of us in public health, it’s rather obvious that the persistent health disparities faced by vulnerable populations are cyclical. Consider the fact that an African American infant born today is more than twice as likely to die within the first year of life as a White infant.[i] While there are some theories that explain this phenomenon (like weathering), we still haven’t effectively addressed the fact that African American infants are twice as likely to suffer from low birth weight, African American women are more likely to have preterm births, or why these inequalities persist for these women despite household income, educational attainment, or geographic location. But what if it’s possible that these disparities in birth outcomes are the consequences of developmental trajectories set forth by the early life experiences of a mother and her child? What if we re-worked the current framework that exists when we think about social, economic, and racial-ethnic disparities in birth outcomes to include the life course?

This is what the Life Course model is all about: the idea that disparities are the consequences not only of what happens DURING pregnancy, but more importantly what happens over the course of a woman’s life. When we think about the fact that homeless women have inadequate access to prenatal care, we need to think about what this means for the their lives and the lives of their children. This isn’t a “homeless,” “substance-abuse,” “African-American,” “poverty,” or “maternal” problem. This is a community problem. And it takes our community to work together to solve it.

Addressing the Life Course for Homeless Mothers and Children: San Francisco’s Homeless Prenatal Program

There is no one elixir to improve the life course of homeless women and their children, but if we consider where we can actually affect the life course of this vulnerable population, it begins in the womb. Unfortunately, prenatal care is not easily accessible by homeless mothers. Everyday obstacles such as bus fare, childcare, violent partners, fear, and distrust can easily come in the way of doctor appointments. Although there are innovative efforts to address these issues across the country at the local and national level, one model has shown to be particularly effective in reaching homeless women and families where they are. We want to highlight the work of San Francisco’s Homeless Prenatal Program (HPP), which provides a holistic community solution to these growing community problems.

Founded in 1989, HPP is devoted to helping and empowering women improve their life course and that of their children. The program connects homeless women to prenatal and health care services, assists them in overcoming issues of mental illness, substance abuse and domestic violence, and assistance in finding sustainable housing, employment, and job training. In doing so, HPP helps women break cycles of poverty, homelessness, and social inequality, and decrease the likelihood that their children unjustly suffer from health inequalities. Last year, the program worked with 3,500 families, and touched the lives of more than 9,000 children.[i] HPP is more than a resource for homeless women and their children- it is a community that is taking back what it means to thrive in the face of adversity. It is a community that can be a model for National-level programs.

Click here to see what it is like inside the world of HPP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_rqGfIeohwM&hd=0

As public health professionals, and as a greater community, we need to move beyond simply looking at pregnancy risk factors, but to early life programming and cumulative stress, racism, and traumatic life experiences over the life course. What if we could ensure that every baby was born into a healthy, safe, stress-free environment? Wouldn’t the future generations of stronger mothers and stronger babies thank us?

[i] Lu, M. C., & Halfon, N. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7(1), 13–30. doi:10.1023/A:1022537516969.

[i] Data in the are comprised of annual point-in-time counts and HMIS data reported throughout the year (October 2009-September 2010). Data are reported based on HUD’s definition of homelessness, which includes people in shelters and on the streets, but not those who are “doubled up” with families or friends.

[iii] Browne A, 1993. Family violence and homelessness: the relevance of trauma histories in the lives of homeless women. Am J Orthopsychiatry 63(3): 370-84

[iv] Bassuk EL, Buckner JC, Perloff JN, Bassuk SS, 1998. Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among homeless and low-income housed mothers. Am J Psychiatry 155(11): 1561-4.

[v] Nyamathi A, Leake B, Gelberg L. Sheltered vs non-sheltered homeless women: Differences in health, behavior, victimization and utilization of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2000; 15:565–572.

[vi] Felkner, M. M., Suarez, L., Brender, J., Scaife, B., & Hendricks, K. (2005). Iron status indicators in women with prior neural tube defect-affected pregnancies. Maternal and Child Health Jour- nal, 9(4), 421–428. doi:10.1007/s10995-005-0017-3.

You must be logged in to post a comment.