Language is a pretty fickle thing. Over time, some words can get so charged that we feel like we have to tip-toe around them. No one likes to say a school is “failing” their students — instead, it’s “underperforming.” Other words can get so mired in one definition that it makes the word limiting. Take the word “violence.” Immediately, most of us think of something like a fight, maybe a beating. The brutality of war probably comes to mind, too.

And there’s a reason that comes to mind – there’s usually a clear “perpetrator” and an obvious “victim.” Our brain is pretty lazy, so we like these easy-to-visualize ways to think about things. And simply put, we can usually think of peace as the absence of violence — peace activists are usually protesting war, police beatings, or even violent video games, right?

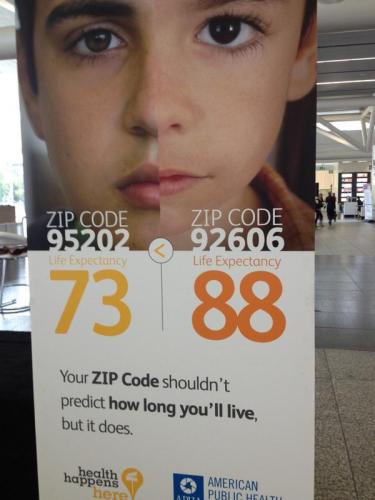

Like we said, language can make some words kind of limiting. About 45 years ago, Norwegian peace researcher Johan Galtung noticed that our definition of violence wasn’t doing anyone any favors. Galtung proposed expanding the definition of violence to mean anything limiting a person’s ability to reach their potential. Let’s use the city of Oakland, CA, and its neighbors to make a point – according to the Alameda County Public Health Department, a baby born in the Castlemont neighborhood in East Oakland will live almost 12 years less than a child born in the much more affluent community of Piedmont. Less than ten miles separate these neighborhoods, but it is night and day. Coinciding with these trends are dozens of indicators; East Oakland also has some of the worst education opportunities, job opportunities, public safety ratings, and community opportunities. Not surprisingly, there are way more liquor stores and way fewer grocery stores in East Oakland, too. In contrast, Piedmont has the seventh best school district in the state of California, and in 2000 had a median family income of around $150,000, or ten times the federal poverty limit in the same year.

We’ve even developed a slogan for this: when it comes to your health, your zip code matters more than your genetic code.

So why bring this up when talking about violence? Because if we use violence to mean physical harm, then we can say Oakland just needs more police, and then there will be peace. But thinking this way is blinding us to some of the most glaring issues. Everyone should be able to live to at least 80 years old; if something is stopping you from living that long, and that something is preventable, then that is violence too. Couldn’t afford health care, and you never got to see a doctor before diabetes took your leg? We wouldn’t normally think of that as violence, but we should. Live in an area where you can’t get fresh fruits and vegetables to make sure your kids grow up healthy? Violence.

It doesn’t have to be one person attacking another — when unequal medical, education, and income access are built into the structure, it is what Galtung labeled “structural violence.” Without this addition to how we think about violence, some pretty limiting environments can still be thought of as “peaceful.”

We need more than “law and order” societies that focus on personal violence and ignore structural violence. That’s because limiting someone’s potential is “violence,” regardless if it’s due to gang violence or a lack of food access.

Unfortunately, it’s easier to measure personal violence — gun-related deaths, drunk driving accidents, and war casualties can be tallied up pretty easily. Structural violence can be harder — “death by lack of access to resources” won’t show up on many death certificates. But unless structural equity is persistently and deliberately identified and pursued through policy change and social action, structural inequity will remain a part of our communities and will increase. We need to reshape how we look at violence, and not content ourselves with stopping personal violence. It may be uncomfortable, but we need to acknowledge that our cities and institutions can be just as violent as any shooting or robbery.

So, how do we live in peace? The Alameda County Public Health Department, UC Berkeley, and over 40 community organizations are teaming together to form Building Blocks for Health Equity. This collective is tackling the structural violence in Oakland head-on, to “create conditions where every child has an equal chance at a healthy and fulfilling life.” This emphasis on the conditions that promote health, not just individual actors, is key to ending the structural violence that can’t be linked to one person or situation. Once we change how we look at the language of violence, we can start on the real work of bringing peace.

Written by Nima Beheshti and Ruvani Fonseka

Sources:

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace and peace research. Journal of peace research, 6(3), 167-191.

http://www.societyhealth.vcu.edu/DownFile.ashx?fileid=1501

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/james-s-marks/why-your-zip-code-may-be_b_190650.html

http://www.pulseofoakland.com/

Click to access 11-19-2013_best-babies-zone-castlemont-neighborhood-snapshot-1.pdf

http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/00poverty.htm

http://www.schooldigger.com/go/CA/cityrank.aspx

http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml